Giving Advice: How to Maximise Benefits and Minimise Risks

Hello there and welcome to Mind Tools. My name is Giulia Bagnasco, I have a background in Organisational Psychology and a passion for applying it to our daily lives.

Mind Tools brings psychological concepts into life through practical examples and challenges for you to try.

“Give a Man a Fish, and You Feed Him for a Day. Teach a Man To Fish, and You Feed Him for a Lifetime”.

Who’s not heard of this ancient wisdom? We can safely say that, at least in theory, everyone agrees that it is much better to teach someone how to fish. Yet, in practice, we all seem very fond of giving out free fish. In metaphor-free words, we are significantly more likely to tell someone what we think they should do rather than letting them reach their own conclusions. But, you may think, is this necessarily a bad thing?

In this article, I will aim to answer this question by focusing on the below topics and, as last time, will finish with a challenge for you to try.

The psychology of giving advice versus coaching

Motivation behind giving advice: the good and the bad (hopefully no ugly)

Conclusion & challenge

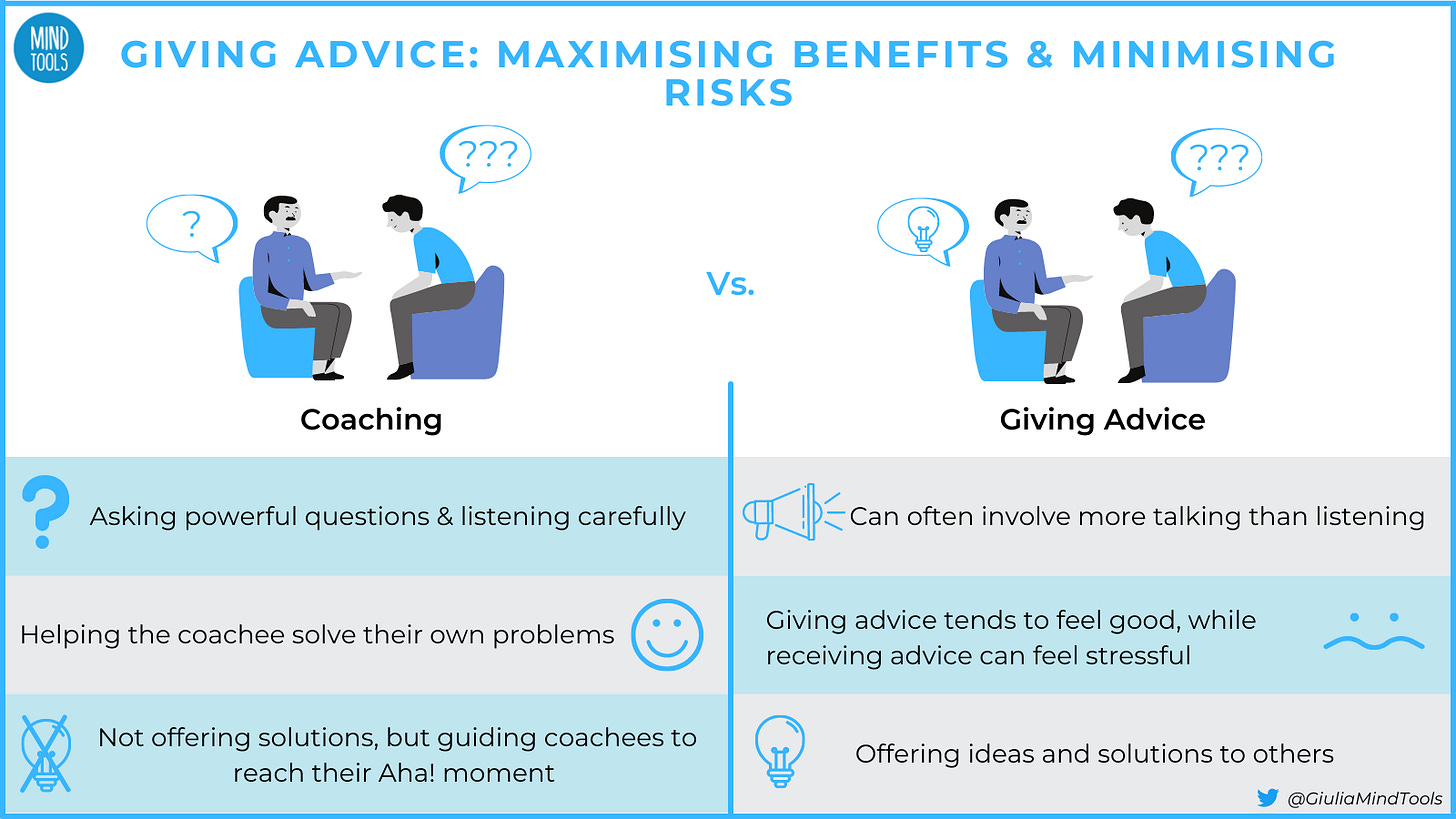

1. The psychology of giving advice versus coaching

Evidence from neuroscience has demonstrated that we are hardwired for altruism. When we help others, our brain literally rewards us through the so-called “happiness trifecta”, a rush of dopamine, oxytocin and serotonin1. For those of you who are not familiar with this trio, these are the neurochemical drivers of happiness that are largely responsible for your good mood.

Without getting into a philosophical debate on the nature of altruism, this technically means that, when you are helping others or indeed giving advice, your brain rewards you through a neurochemical reaction that gives you pleasure. In layman’s terms, when you give others advice, you feel good.

According to some, coaching is the polar opposite of giving advice2. Instead of telling someone what they should do, a coaching conversation involves listening carefully and asking powerful questions. In this case, the ultimate objective is for the individual to reach their own conclusions and solve their own problem.

In a nutshell, a coach does not offer solutions, but, through listening and non directive questioning, helps others reach their goals. And here is the twist. Neurology research has shown that finding insightful solutions to problems also releases mood-enhancing neurotransmitters3. So, where does this leave us?

In summary, giving advice/telling someone what they should do makes you feel good, while letting others reach their own conclusions makes them feel good. According to this argument, giving advice is selfish, as you are depriving others of the feel-good neurotransmitter rush so that you can feel it in their place.

But is giving advice really always a selfish act?

2. Motivation behind giving advice: the good and the bad (hopefully no ugly)

To answer the above question, no, giving advice is not only classifiable as Satan’s pastime. For starters, both in our professional and personal lives, we are often asked to give advice. In these cases, obviously, there is nothing wrong with sharing your thoughts and wisdom. However, when it comes to unsolicited advice, the key differentiator between “good” and “bad” advice is often down to the advice-giver’s intentions. Let’s explore these distinctions.

The good

Sometimes, even if someone’s advice doesn’t exactly fit with our values or the specific situation, it still feels good to receive. Usually this is because we can feel that the other’s intentions are genuine. For instance, you might be offering your advice because you think you can help. Especially if you are hearing others speak about a problem, you might make suggestions because you want to make their life easier or reduce their stress.

Even if what people usually need most is to be listened to and supported (sometimes all we need is venting!), we do have the tendency to assume that others are looking for answers and hence feel a drive to help them find solutions.

Other times, you may have found something that works for you and cannot wait to share it with others so that it can help make a positive impact on their lives too. This is particularly the case when your challenges or situations are similar and, as a result, you assume that your solution will equally benefit others.

Clearly, in both these examples, your intentions are good and, as long as you provide your advice respecting the other person and you are ready to listen to them and their needs, this form of advice can only be encouraged!

The bad

Of course, we like to assume that we are always operating with good intentions. However, we are human and, to varying degrees, we can be rather self-indulgent or judgemental.

Personal life example — self-indulgence

Imagine that you have just been through a strict diet and exercise regime and that you have lost a significant amount of weight. You can finally fit into that pair of trousers you thought you had to give up on and, frankly, you are feeling great about yourself.

Now, your friend is complaining to you on the phone about how she’s unable to lose any weight, she’s telling you that she’s feeling terribly self-conscious about the way she looks. The temptation to start a monologue about what she should and not do is strong. After all, your recent success and experience is very relevant here and you might feel compelled to share your wisdom. Before you do so, I invite you to stop and think for a moment.

What is really your intention here? If you really look within, do you want to help her or do you want to show off your achievements? If the former, the best approach is to ask her if she does want to hear your advice. If she does, then, by all means, do tell her what’s worked for you and how you have made it work.

However, if your underlying intention is not so pure and you find yourself listing all of your techniques and successes, I do invite you to stop. This does not mean you are a terrible and selfish person. We are all guilty of a little self-indulgence, but what we need to keep in mind is that unsolicited advice can generate stress. Instead of helping her, you may be in fact making her feel helpless.

Professional life example — judgement

Let’s imagine another scenario. You are having your regular 1:1 with your junior co-worker, with whom you have a friendly and trusting relationship. Five minutes into your conversation he starts to complain about his boss who, lately, has been ignoring him, cutting him out of emails and not inviting him to meetings. He’s very frustrated and starts sharing several examples, sounding more and more upset.

You have worked with his boss before and have never experienced this behaviour. If you are honest with yourself, you think he’s over-reacting. Most people would feel tempted to give him a few directions on how he should tackle the situation. But, before you do that, I nudge you to think about your colleague’s needs.

Is he asking for your advice or does he want to be listened to? What is really causing you to want to give him advice? Is it because you want to help him or because you feel like he’s being immature and over-emotional?

Chances are that, in this case, he wants to be listened to. It might be most helpful to ask him probing questions to help him get to the bottom of the issue and to give him a chance to blow off some steam. Obviously, if this reaction is a frequent circumstance, a little tough love might help him; however, in most cases, the best you can do is listen to him and ask questions. If he wants your advice, he will ask for it himself.

3. Conclusion & Challenge

Is there a dark side to advice then? As a good psychologist, I’ll have to answer with the usual “it depends”. If you only read the first paragraph, you might think that I’m trying to persuade you to give up advice in favour of coaching. While of course active listening and powerful questioning are a fantastic duo, I do not suggest we should throw advice out of the window.

Great insights can come from receiving advice from family, friends and colleagues (or strangers!), even if unsolicited. However, what you should always be wary of is the intention behind the advice, both when you receive it and when you feel like giving advice.

My challenge for you is that, next time you feel ready to give someone advice, you stop and think about your intentions. Instead of jumping straight on, ask the other person whether they would like your advice. It sounds simple but it can go a long way, I promise.

If you liked this article, why not share it with your friends and colleagues so that they can also try this challenge?

References

Inagaki, T., Bryne Haltom, K. (2016). The Neurobiology of Giving Versus Receiving Support. Journal of Behavioural Medicine. 78(4). 443–453.

Hastings, L. J., & Kane, C. (2018). Distinguishing Mentoring, Coaching, and Advising for Leadership Development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2018(158), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20284

Tik, M., Sladky, R., Luft, C. D. B., Willinger, D., Hoffmann, A., Banissy, M. J., Bhattacharya, J., & Windischberger, C. (2018). Ultra-high-field fMRI insights on insight: Neural correlates of the Aha!-moment. Human Brain Mapping, 39(8), 3241–3252. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24073